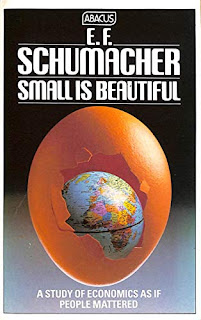

Small is Beautiful Part 2

This was meant to be the post. Honest. A look at E.F Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful as an explainer of the underlying philosophy of the Campaign for Real Ale. Explaining why the preference for small breweries and independent pubs. Explaining why went on longer than I expected and it’s bloggery so there’s no editor crossing stuff out.

Part 1 of Schumachers book addresses what he sees as the

modern world. In 1971. From production of consumer products (like beer!) to

national issues of peace and war, the role of economics, a diversion into Buddhist

economics (yeh really, imagine that) before tying it up with a question of

size. In the first chapter, The Problem

of Production, he argues that the modern economy is unsustainable. Natural

resources (fossil fuels), are treated as expendable income, when in fact they

should be treated as capital, since they are not renewable, and thus subject to

eventual depletion. Schumacher's philosophy is one of "enoughness",

appreciating both human needs and limitations, and appropriate use of

technology.

Reading it you get the idea that he’s decided his conclusion

in advance. He thinks big companies are bad, small companies are good and I’m

expecting his rationalisation for believing this. But it isn’t really isn’t a

reasoned conclusion. It’s a belief, not rationalisation. It’s a romantic idea

that before large national corporations things were better. It all went wrong

with the formation of the 1st joint stock company. It’s like when a

CAMRA person tells you microbrewed beer is better in an independent pub when

your own tastebuds are telling you “maybe somewhere but not in this pub, pal”

There exists a romantic idea that in the past we were all

free and lived idyllic lives and made all we needed by hand and were happy in

our mud huts. We hunted and gathered and weaved baskets and made sprout wine

and had nice naps in the afternoon after a bit of afternoon delight. We

weren’t. It was cold, miserable and we were hungry and we died young of

diseases we didn’t understand believing gods had smited us for not sacrificing

our livestock/pets/children to them. Society evolved into serfs and lords and

most people were serfs. That’s what motivated us to invent the things that made

life better. Things were shit, we made them better, we continue to make things

better because things that are still shit annoy us enough to want to change it.

Progress. Schumacher likes the past and want us to return there. This is the

point where I saw the appeal of the book to King Charles. Why this was such an

influence on our organic farm loving gentleman farmer King. It’s basically a

romantic view of feudalism. Which it’s possible to have if you’re the King.

It’s less romantic if you’re one of the serfs.

Schumacher makes a number of bold assertions he doesn’t

really back up. That large companies are more wasteful of natural resources and

energy than small factories of manual rather than machine labour. This isn’t

true. Or rather he doesn’t back it up with “here’s the example”

I found myself thinking of examples of my own. Let us say

meat. We love the idea of a small farm of happy animals treated well. The

bigger it gets, the more industrial, we think the animals are treated worse. As

units of production, not living things. We are right to think this, it’s true.

It’s immoral by the systems of ethics that have evolved in a society to which

we all subscribe even if most no longer subscribe to the underlying religious

theologies that underpin those ethics.

In an economic sense there is also what is known as the

externalisation of costs. Transferring costs to society rather than reflect

them in your operation. Animals produce waste. To be vulgar they shit. In

traditional farming this is not a problem. It’s all fertilizer for fields. On

an industrial scale there is just too much of it. It becomes a toxic pollutant.

A large industrial farm needs its own sewage facility. That’s a cost. Otherwise

it pours all the shit into the river, it kills the fish and all the little

animals middle class people like to see on BBC2 programmes. Large companies can

lobby politicians, shape the law in their own favour, externalize costs and

make all us taxpayers pay to clean up their mess. There’s an argument in favour

of Schumacher. But I made it myself. He didn’t give it to me. I was expecting

him to. Examples to back up his reasoning

There’s arguments against Schumacher. You have to explore

those even if your only purpose is to refute them. In beer as our example, many

think that “local” small batch beer is better for the environment. What if I

told you energy efficiencies were gained not by putting lots of small boilers

in in lots of sheds, under railways arches, and industrial estate lock ups, but

in large factories.

These large factories are able to better measure at each

state of the process the inputs and the outputs. Those “evil accountants”

cutting costs are making incremental marginal energy savings that add up to a

significant energy use difference between a Macro lager and a Local Craft Ale?

That to be big is to be able to measure a process and improve it and reduce the

environmental and financial bill by small regular incremental changes. Innovation

and progress. To be small and manual is to just keep shoving the grain in the

boiler and moaning at the size of the electricity bill. To be big is having a

department analysing the costs of each stage and reducing them.

On distribution, there are positives to size. Logistics

being a tool of large companies. This means a large multi nationals can

distribute beer around the world at the lowest environmental cost and return

the containers to source. A complex system of working out routes and filling up

trucks to capacity reduces the environmental cost of distribution. Employing an

administrative layer of people and computers.

Far better than the craft solution of plastic one way

disposable “key keg” containers that advocates insists “can” be recycled but

never provide proof that they actually are. Plastic Key kegs are an

environmental disaster. Complex objects of differing materials that would need

to be disassembled and categorised before separating into differing high energy

recycling streams where they produce plastic of a lower degraded grade. There

are people that actually advocate key kegs as environmentally friendly? WTAF.

Twitter is full of these idiots. They’re the ones buying and selling this stuff

to a consumer base that like environmentalism and recycling and they are

distributing their beer in the least environmentally friendly way you can think

of.

It's the likes of Heineken, lads, the big boys that can

afford depots, lorries, and IT departments, that build a system of global

logistics that transport a keg of beer on a truck halfway around the world, and

back again at the lowest environmental impact because that’s also the lowest

financial cost. Every truck full, no mile wasted, all worked out by people on

computers not people manually shovelling grain into a boiler with a spade

because that is a more fulfilling dream. Big companies working out the most

environmentally friendly way of taking a thing from one place to another.

Okay, Schumacher was seeing the world in 1971, not 2023, but

come on. His contemporary believers, this is 2023. Just admit your key kegged

craft beer is an environmental disaster but you like it and think its worth

polluting the planet for. I’d respect that more than trying to make out small

is environmentally better. Schumacher is, you see, short on the detail of how

and why a small production facility might be environmentally better. It’s just

something he believes to be the case. Like his contemporaries today. It’s what they

believe.

When he delves into world peace and the absence of it, we

see more of his faith-based arguments. Though clearly of a Christian background

he’s read a bit on Hinduism and Buddhism to chuck a few quotes in, but you

don’t get the impression he has particularly understood these faiths beyond the

fact that josticks and yoga was a thing in and around that time and maybe he’d

listened to a George Harrison album.

Schumacher admires the East, because they are poor. He

notices the polythetic religions of the East, like the monotheistic religions

of the west tell people they should be happy being poor. He assumes they are

happy being poor, what with them being poor. How noble of them. We should be

more like them. Time has not been kind to this argument, the economic progress

of India & China and the mass migrations of people from dirt poor parts of

the world to the rich west would seem to indicate he hasn’t quite nailed that

one. People don’t like being poor. People want to be rich. People like things.

People want things. Things make people happy. Give people things.

I am less scathing on his chapter of Buddhist economics, of

which of course, there is no actual such thing. It’s a term he made up to

explain village economics. But what he imagines this to be is a harmonious

economy of production by renewable inputs and realising none renewables ought

to be treated as capital rather than income. Fair enough. Norway did this. They

turned their oil into a sovereign wealth fund, capital. We treated our oil as

income and spent more than we taxed. I’m not disagreeing. I’m with Schumacher

here. None renewable inputs ought to be considered capital rather than income

in any economy. He just doesn’t explain how his small village economies would

do this.

He makes no argument as to why or how small companies are

any different to large in the use of our natural resources. None at all. I’ll

make my own, then? Consumer pressure maybe? But here I’m creating my own

examples. He hasn’t thought it through.

A question of size is sublime. The book is of its time. Back

when the left hated the EEC (what is now the EU) and the Tories loved it.

Therefore there is no love of Europe, Thems the bad guys. But it’s because they

like big companies and product standards and economic growth. But his argument

here breaks down into little more than working for a big corporation is soul

destroying and being a bit more hands on and connected to producing what you

consume makes you happier and give your life meaning. A fulfilling life is

brewing your own beer and weaving your own sandals. Or walking to the micropub

in your home weaved sandals to trade a newly weaved sandal for a pint of the

landlords homebrew. If he wants one for the other foot, that’s another pint,

mate.

Schumacher appears to believe this from things he’s read,

not things he’s done. A bureaucratic job is soul destroying because he read it.

He’s never done one. It’s not his experience, it’s his interpretation of the

Kafka’s The Castle.

But is he right about work satisfaction? I have some

personal experience. I work. I continue to do so long after it ceased to be an

economic necessity because it gives my life purpose, direction, interest and

satisfaction. I like pissing around with computers. I like that people pay me

for it. I like that this means I can buy all the things I need and not have to

make them or do them myself. I feel no shame in admitting that I’m pretty

useless at a lot of things and would not or could not do them well. I’m good at

computers and databases though. It’s handy in life to be good at something

people will give you money for. Maybe I’d be good at other things if I tried but

Clive Sinclair invented the zx spectrum when I was a kid, and that was me sold.

I know my stuff there.

So a world where someone else builds me a car and services

it works for me. A world where some blokes come around and fit me a new

bathroom and my job is to buy a mcvities biscuit selection box and put the

kettle on works for me. A world where someone want to chuck the monetary tokens

at me to pay for all of this just because I understand computers works for me.

It is satisfying to do something you enjoy and get all the material things you

need and want. Cheers, this corporate world with division of labour is not a

dystopian hell. This is a world better than it was and we have it better than

our ancestors and we ought to thank them for making the world this good. We

should accept our responsibility to make it even better for the kids coming

next by inventing lots more cool stuff like bigger chocolate bars, a cooler

iPhone and self-cleaning toilets. Not condemn them to a feudal and poverty

stricken past of organic vegan farmers markets where a bottle of wince inducing

home brewed pea pod beer sets you back a days pay.

I don’t want to brew beer. I don’t want to serve beer. I

want other people to do that and bring it to my table. That works for me. I

would not be more satisfied and happy if I had to make my own beer in my own

shed. That would make me less happy.

I’ve made my own beer. In a plastic bucket, from a can

bought in Wilko. It was ok. It wasn’t as nice as what Tesco will sell me. I’m

happier with the box of old speckled hen I bought from Tesco, thanks. It means

I spend my time doing things I enjoy like writing SQL, winding people up on

twitter and less of what I don’t like, like mopping the kitchen floor for the 3rd

time because apparently it is still sticky and I didn’t clean it properly after

I stunk the kitchen out making that horrible beer I pretended to like. “It’s

not spilt beer my love, I think this kitchen floor is naturally sticky, it’s

the materials it’s made of. Maybe you should go in that German Kuchen Haus

place on the A6 you were banging on about and pick a new kitchen. Take my

credit card off the kitchen table. Ask for one without sticky floors.”

This belief based on small being better persists. I’ve heard

the Schumacher story of soul destroying corporate work before. I heard it in a

CAMRA meeting. A microbrewer called Toby was telling us all how his well-paid

job in finance rotted at his heart and he loved making beer in his shed. Now he

has a bigger shed but still small enough not to be evil. He’s now living his

dream and making interesting and artisan beer. We can support his dream by

buying his beer. And the story resonated with all present. This was indeed the

dream, small artisan craft brewers. Support the dream. Buy this beer. To be

fair, his beer was nice. But he wasn’t selling beer. He was selling a story and

people bought the story and bought his beer.

Toby was a better story teller than Schumacher. He did a

better gig. But then again Toby handed out free beer and seemed an amiable sort

of likeable chap as people that give out free beer often are. Pretty much every

meet the brewer presentation is Schumachers story re written as a first person narrative.

It’s a compelling story when told this way. You want to root for the guy.

It’s still bollocks, though.

In the next part of Schumacher’s book he bangs on about

resources, then, the third world, then concludes with size and ownership. And

size does matter. Only he likes it small. So there’s more to say on this in the

next blog.

Comments

Post a Comment