Small is Beautiful Part 1

What? This was meant to be a beer blog. About beers that rarely get a mention but seem to sell and pubs that also rarely get a mention because they don’t quite appeal to the middle-class enthusiast. Not just keg boozers but pubs whilst seem to hold a cultural place in society but are largely ignored by enthusiasts or campaigners.

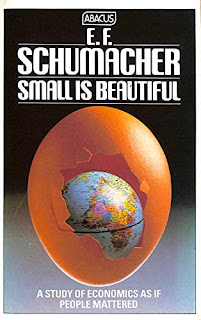

This is none of that. It’s a short series of blogs about

CAMRA and a book I’ve read. E.F Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful. There are no shortage of beer blogs that seek

to criticise the erstwhile CAMRA brigade for something or other. Either for

campaigning for something or not campaigning for something or maybe they are

just too pale, male and stale? Or maybe they gave a beer gong to a beer or pub

you think they shouldn’t have? Abbot Ale? Heh ho. This is not it. It’s not a

slagging off. It’s not praise for what they do. It’s an attempt to understand

them. I rather like CAMRA. My experience of CAMRA is one of a nice, sincere, well-meaning

group of largely harmless, mostly middle class, mainly left-wing, people

engaged in a hobby they love and cause they are passionate about. You may agree

or disagree with something the organisation says or does, but there is little

to dislike about them. Even the more eccentric members are harmless

entertainment.

This series of blogs is about my attempt to greater

understand the underlying philosophy of CAMRA and its members through reading

an economic text from the early 1970s. Why make such a strange connection and

what would those questions be?

CAMRA was born in the early seventies at a time when other

similar type of social movements were cropping up. 2 types of middle class were

emerging. A middle class that emulated the trapping as far as it could of the

wealthy and a middle class that wished to reconnect to an imagined rural rustic

idealistic past. The connection to the social movements of the 1970s, of which

CAMRA is part of, to Schumacher’s work ought to be undisputed. Here is a book

rationalising these ideas as an economic text in and around the time they occur.

Was Schumacher rationalising ideas that were already part of the zeitgeist or

expressing ideas to influence or create a zeitgeist? I wasn’t there but I like

economics and had never read this work. So that’s a reason all of itself.

CAMRA was formed in 1971 and as you might expect was a

product of its time. Its success as a membership organization has over the

decades occasionally caused it to question its purpose and direction. The

degree to which it has developed to meet contemporary needs and views I’m not

going to answer here but at the start it arguably was a product of its time.

Some connect the early 70s zeitgeist to a picture of Earth

from the moon, known as Earthrise, that presented a view of our planet as a small

vulnerable ball in a vast nothingness. If we don’t look after this place and

the plants and species on it, we’re screwed. There ain’t anywhere else. Fair enough.

That time saw the beginning of a number of movements that

appear related in values and appear to attract a similar type of person. The

organic food movement. There was and remains a campaign for real bread as well

as the one for beer. It appears similar. They don’t like mass produced bread

and want you to buy artisan bread from a bakery or bake it yourself. That was

before there was a pandemic and a lot of middle-class people staying at home.

The homebrew and allotment trend of the 70s, connecting people back to the

produce you eat in your suburban home. My Dad did all of it. Wore flares and

grew carrots in his back garden, made wine from cans bought in boots in a

demijohn. It was a thing. If you grew a vegetable that looked like genitalia,

there was a show on Sundays called That’s Life that would show your amusing

vegetable to the nation. My mum liked it, my Dad thought it vulgar, my sister

and I were with Mum. That didn’t stop him saying “here son, look at this one”

when he grew a carrot that looked like a cock. This leads into the political

sphere where we see the development of environmentalism and the green party as

people form the view the natural world is something to preserve, not exploit,

and that maybe we have lost something by disconnecting ourselves from the

production of agriculture to live in urban environments. A romanticising of the

back breaking hard work and the hard short lives of peasants and serfs by free,

educated and comfortable people. A strange desire to return to something that

those trapped in it, cannot wait to escape, and work hard so their children

don’t have to suffer. The first generation really in history to know a

prosperity never before achieved, a comfort never before attained wanted to go

camping in a cold wet muddy field to reconnect with nature, eat cardboardy

bread like in the past and drink beer that kicked you back.

Next, the questions I sought clarity on. I have been a

member of CAMRA and been to meetings and seen the decision-making processes

that create the awards and entries into the books and magazines. All

democratically decided by all present. But all present strangely of a similar world

view. As you’d expect maybe, from a self-selected group that thought

campaigning for real ale to be a worthwhile use of time. There were times where

I had so many questions as to why a rational sensible group of educated people

would do something they did that appeared counter-productive to their stated

aims. Not that they were not entitled or within their rights. I was left with a

framework of psychology. Group behaviour, group dynamics. The ability of groups

to reinforce bad ideas because supporting a bad idea confirmed status and

position within a group structure. I’d learnt that at university where the bay

of pigs in Cuba got mentioned a lot as the example to regurgitate in an exam. Was

that that the reason they all knowingly voted for a crap beer pub to win a

gong?

Certainly, that explained some of it. It wasn’t hard to see

those that sought the approval of others in what they voted for in meetings or

beer scored on a pub crawl. Natural normal human behaviours in hierarchical

tribes. Whether monkeys eating bananas in a jungle or old men drinking bitter

in a pub. The group psychology is the group psychology.

I attended a CAMRA meeting at a multi beer pub that was off

the well-worn local circuit and suffered poor turnover. Despite poor beer

quality and a stated culture of “take it back” no one did. No one bought a

second drink at the beer break. At the end of the meeting everyone left quickly,

no one lingered as they tended to in a multibeer free house, half-drunk pints

were left. The belt clip tankard zz top cohort were pouring bottles of German

lager into their tankards and making an effort to do it out of sight of the

wider group. From previous experience, in another pub, one or two would have

led the others in taking it back and getting barrels changed. That was odd. Odd

enough to remember. Behaviour out of the norm and alongside self-awareness of

expected norms. What occurred next gave me questions I could not answer.

What surprised me at the next meeting was that very piss-poor

pub winning a local pub of the month and people voting for it that had been at

the previous meeting and complaining to each other about the beer they left

undrunk. It was a pub that required support, they agreed. It was an independent

free house. It had many microbrewery pump clips. It was worthy. It had terrible

beer. Eh? I’ve questions, as they say.

There was something beyond group dynamics and people

following the crowd I simply did not appreciate.

The level of anger, among some of the longest standing

members, I saw when a chain pub or a Sam Smiths pub, in both cases serving

decent beer and populated by a general public you’d think CAMRA would want to connect

and communicate with, wasn’t a case of group dynamics but of a principle I was

not appreciating. One beige dressed chap kindly explained to me that “those are

not the sort of pubs we are about” this was revealing. CAMRA members, as I’ve

said, are nice people. If you talk to them and listen, they will reveal to you their

underlying beliefs. Not only what they think but why they think it. And they

will do so in pubs that are quite nice to sit and drink in.

So why the clear preference for microbreweries, micropubs

& independent free houses? Its not just a belief that they produce better

beer or beer produced more to their taste. I’d seen abjectly terrible multibeer

pubs with rotten beer win CAMRA awards on multiple occasions. I’d seen fierce

resistance to suggested awards for chain pubs selling great quality pints. What

was all that about?

There is a clear underlying bias toward small microbreweries,

independent free house pubs. More than a case of “they are the ones that

produce the beer we like”. There was a principle here. A principle I have

wanted to understand better for quite a while. Pubs that met a particular set

of attributes were favoured over pubs that didn’t. But what were those values?

Small and independent and selling lots of different beer, as I understood it. A

pub with those 3 qualities selling a range of microbrewed beer were scored and

appreciated more favourably than a tied house or chain pub with a great pint.

Why was this? Why was the language of morality so often invoked by members keen

to “support” one delivery model over another?

Why then the view that microbrewed beer is a morally more

virtuous product than a beer made in a large production facility? The former

might be knocked out by a bearded sex pest making only himself rich as he hawks

his prospectus to Heineken whilst selling soon to be worthless shares to beer

geeks? The latter in a giant clean factory following all laws and regulations,

paying its tax and paying its dividends into the pension funds that underpin

the retirement plans of millions.

Why the view that an independent free house is a morally

superior system? It’s a private fiefdom of its owner running a gaff by his own

rules good or bad. The large chain has a HR department and ability to offer the

teenage recruit a career path and formal training and day release to college.

It is audited and given a level of scrutiny that tends to keep the company

within the bounds of societal expectations. The teenage girl has arguably

better protection and somewhere to complain to in the large chain if and when

her manager makes an unwanted sexual suggestion and pats her arse. Is there no

acceptance that the large company can be better?

The CAMRA I encountered had an underpinning. Small is

better. Small breweries, independent pubs. It was a given. Why?

Much of my awareness of these 70s cultural trends started

with the repeat of 70s TV shows in the mid-90s. The type of shows which are now

repeated on digital channels and often come with a warning about showing

outdated cultural references that some may find offensive. Though much of that

appears, at least to me, to be a misunderstanding of the difference between

showing a bigoted character to mock the stupidity of bigotry and that of

endorsing bigotry.

So, my awareness doesn’t begin with an appreciation of these

movements, it begins with comedy that gently and affectionately mocks it. The

Good Life being the most famous. A disaffected man convinces his wife to become

a small holder farmer in their suburban back garden and give up working for

money and instead grow vegetables and barter for anything else they need. They

ferment their own wine from the things they grow. A show on the absurdity of

abandoning modern life, mass produced products for an idealistic agricultural

past that reveals the backbreaking hardness of it and also reveals that all to

often they are actually reliant on the goodwill of their more prosperous neighbours

and friends next door to help them out. A show that that equally mocked the

pretentiousness of the conventional aspirational middle-class neighbours,

Margot & Jerry, with their rustic back to nature middle class neighbours

baking artisan sourdough. Though this wasn’t the show that had most impact on

me.

The fall and rise of Reginald Perrin was and remains the

funniest sitcom ever written. A dark tale of a disaffected middle-aged man

taking increasing risks with his life that may lead to happiness but could more

likely lead to disaster. I have no reason to love it. I first watched it as an

optimistic undergraduate student looking forward to the paycheques a corporate

world might offer me. Maybe it was Leonard Rossiter’s performance, maybe his

inner world revealed through fantasy scenes, maybe even the hint of darkness

offering a texture uncommon in sitcoms.

A story of a man either about to change his life or commit

suicide. There is no significant reason for his unhappiness. He has what many

would want. A nice home, a nice loving dutiful wife, a well-paying job. At the periphery

he is surrounded by, from his perspective, idiots, but these are minor inconveniences

that circle an otherwise decent life. To Reginald they have more significance

than they ought to and lie at the root of his unhappiness. Or are they really the

root of his unhappiness or just the focus of where Reggie chooses to place an existential

angst that is at the heart of the human condition and cannot be fixed, only

accepted? All of the (from Reggie’s perspective) idiots are sublime caricatures

of the time. I could mention Great and Super or even Geoffrey Palmers turn as

the right-wing former soldier. It is his son in law, Tom, I shall turn to.

Whilst the story arc of Reggie is one of him abandoning his

safe corporate job and eventually setting up him own small shop, only for his

small micro business to be ruined by success as his success takes him once more

into corporate life, I’m going to mention Tom. A lugubrious, sanctimonious man

lacking self-awareness that makes homemade wine. A lurid coloured drink named either

sprout wine or pea pod wine depending on the scene and always drank with a

wince, whoever is drinking it. A send up of a trend at the time for home made

wine. There was something about this character I remembered years later when I

encountered CAMRA members and saw an almost religious rather than reason-based commitment

to small production microbrewery beer that seemed unrelated to the actual

quality of the beer produced. I saw Tom wincing at his own lurid concoction

when I saw CAMRA members debate, and was invited into that discussion, an apparently

intentionally sour barrel of beer that made them all wince.

It was Tom telling me a microbrewery beer was intrinsically,

morally even, a more righteous product that something made in a large macro

brewery. A view that appeared unrelated to any attribute of the beer you might

associate with quality or consistency. The microbrew was better, even if it

smelt funny and every character winced when they drank it. It is always Tom I

see when I encounter this view.

So, I encounter this movement one generation removed where

the cultural legacy is one of a gentle affectionate mocking of it. Not a direct

experience of it or even the imperative or dissatisfaction that spawned it. Which

you might think gives me a sort of prejudice rather than open minded

understanding when I come to read this book and see whether it is as I have

been led to believe, a foundational treatise of the values that underpin all

those movements that seek for us to abandon our mass produced products and

lives and return to a simpler maybe more fulfilling life of having less but

being happier with it.

I will go into detail, but a fair summary of this book is

that Schumacher doesn’t like large corporations and mass-produced products. He

thinks man serves the economy and the economy ought to serve man. Fair enough,

pal, in that sense I’m with it.

He thinks we would all happier if we abandoned our current

economic system and started an economy of small companies, producing less. Not

socialism. More a return to an idealised romantic past of small production and

meaningful skilled artisan crafted work. Artisans trading their produce with

each other in a marketplace. We’d be happier, more fulfilled, more connected to

our environment. We’d live in harmony with nature and stop depleting our

natural resources. We’d stop buying new shirts and learn to sew a button on,

we’d stop drinking mass produced lager and instead all sip and appreciate the

ale of local artisans. Not just beer but cheese and chutney too. The whole

caboodle. Out with coco pops and in with porridge. And no not chocolate ready

break or honey golden syrup porridge but the horrible real porridge without

sugar. No more factories and production lines of ping curries and pizzas but

every household chopping and preparing things they’ve grown themselves or

bought from local small producers. Lots of turnip soup, then, and homebrew

beer. Maybe sprout wine. The drudgery we’ve escaped, returned to give us a more

fulfilled and meaningful life.

Its an argument not just for microbreweries but for micro

everything. Thus is my long rambling introduction to the next 3 blog posts

regarding Schumachers Small is Beautiful. 3 because the book is in 4 sections,

and I’ve written a rambling over long explanation. The modern world, resources,

the third world.

Of course, Schumachers the modern world isn’t really anymore.

It’s the world of the 70s. But this is the underpinning idea that has been

retained. What has merit? What never had merit? What now only looks good or bad

with hindsight? Why still believe this nonsense? That smaller production

facilities are better for the product, the person and the environment. What’s

it got to go with beer and our friends in CAMRA? That’s all coming up, from next week. Join me for a delve into Schumacher's world of the micro-everything.

Brilliant stuff. Waiting for the next three parts.

ReplyDeleteGood stuff, Cookie :-) CAMRA was very much part of the Good Life zeitgeist.

ReplyDeleteLove to know where the off-the-beaten-track multibeer pub was.

Since at least the late nineteenth century there has been a reaction against modern industrial society and its culture in art, architecture, design, economics and politics, and a yearning to return to an idealised form of pre-industrial rural existence based on associations of small farmers and artisans, on both the left and right: the socialist followers of William Morris in the Arts and Crafts movement, certain strands of British fascism and National Socialism in Germany, and the Catholic economic theory of distributism championed by G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc.

ReplyDelete@Matt Certainly, Matt, a desire to return to a more rustic way of life predates the 70s zeitgeist. I kept my points to the 70s as I considered earlier reactions to be associated with the urban squalor of early industrial society. By the 70s, squalor was not part of the respectable working class / maybe even lower middle class life. Certainly not the family i grew up in. This was a reaction against comfort and prosperity, not a reaction against the squalor the labour movement did much to remove. It wasn't posh people looking in horror at dark satanic mills. It was a prosperous post war generation enjoying prosperity and comfort saying "centrally heated heated with full english? Nah. gimme a tent in the cold and rain and a bucket to crap in"

ReplyDeleteBy the 70s movements were cropping up, Schumacher published this book and CAMRA was one of many. Whilst I hope you tune in for the next parts one thing I haven't figured out you might have an opinion on.

The degree to which Schumacher is rationalising something that is occurring and in full swing to the degree he he influencing and inspiring the creation of these movements.

Parts of the text seem to lead me to maybe a bit of both. He's rationalising ideas people have and giving a logical framework to it whilst also spreading the idea to inspire exactly the type of students and recent graduates that saw a reflection of these values in groups like CAMRA. A reinforcing circle if you like.

@mudge I could do that Mudge. The pub is now closed and a slagging off of a functioning business wasn’t my point. That year at least 3 pubs/bars got awards that had poor beer, acknowledged by people who voted for the pubs but thought them worthy. So the tale serves not as a "this pub is crap" but the revealing of a bias or preference (nicer term) for a type of outlet.

ReplyDeleteMy point may be disputed but in my view I observed a clear bias towards independent free houses and micro-breweries. Not just in voting. I could have made the point that beer scores did not reflect a quality standard but preferences of the scorer and if all your scorers have that bias that reveals itself with scores that are not reflective of beer quality.

Great stuff. I think that supporting worthwhile enterprises in principle, should be separated from supporting crap beer in fact. Hopefully a trap that is easy to avoid with the sort of common sense that many CAMRA types lack.

ReplyDeleteCertainly the irony of some behaviours needs to be pointed out. That's why you won't find me paying top dollar for overpriced shite beer as a matter of pri.

Missing word. Principle

ReplyDelete